|

Europe and the euro are living on borrowed time. Greece may dominate the conversation now, but it is just a symptom of a larger, structural flaw that threatens the long-term survival of both the European Union and the euro. The euro was created at the turn-of-the-century to do two things: 1) end the punishing wars that plagued the continent for thousands of years, and 2) compete with the fully-integrated economy of the US. The creators of the euro believed European nations united by a common currency would find fewer reasons to attack each other. Joining forces economically would also create an economic trading block to generate a combined GDP bigger than America. EU nations may not be shooting at each other, and European GDP has exceeded that of the US, but that doesn’t mean the euro is a success. In fact, if things keep moving in the same direction, the euro experiment could end up being a disaster.

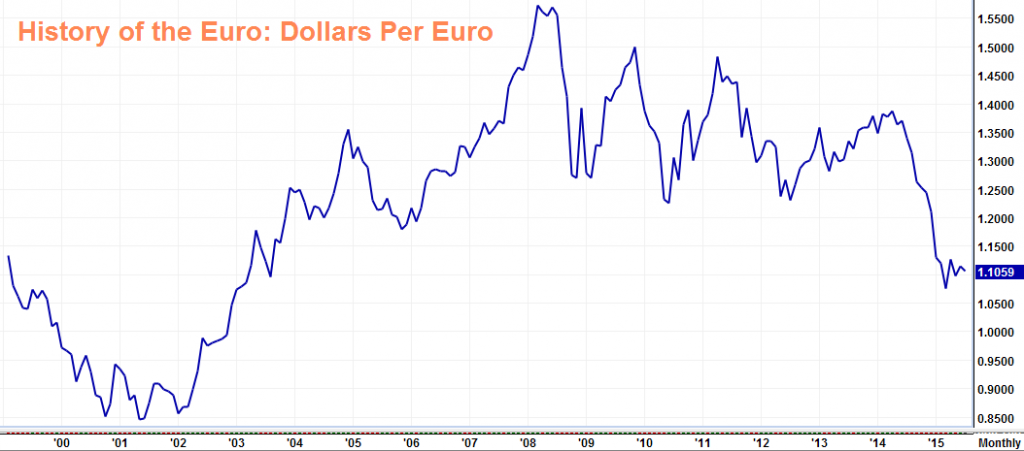

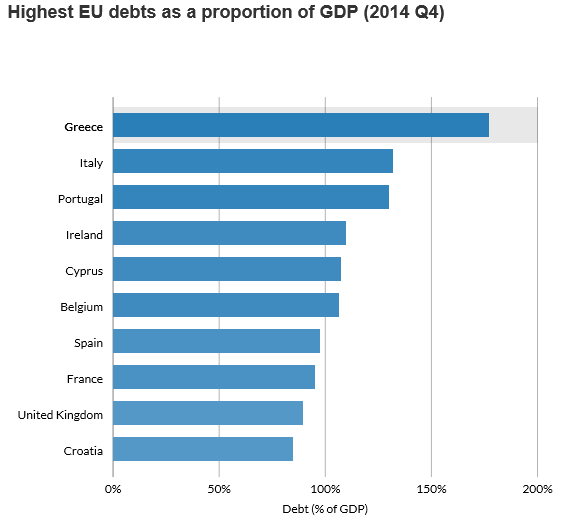

The chart above shows the entire history of the Eurozone’s common currency. The euro was born in 1998 at roughly $1.18 and immediately fell to 85 cents. The “dot com” boom was in full swing and the US dollar was king. The new euro was untested and untrusted and the American economy was booming. Then the bottom fell out of tech stocks, dragging the US economy into a recession. Alan Greenspan and the Fed responded by cutting interest rates to the bone. This led to the housing bubble and even larger interest rate cuts that finally culminated in the infamous bond-buying mania we know as Quantitative Easing or QE. The euro soared during this period – not because it was a great currency – but because euro-denominated deposits paid far more interest than US deposits due to artificial interest rate suppression by the Fed. Europe finds itself in a similar position now. Mario Draghi and the European Central banks are suppressing interest rates just like Greenspan. And they are doing it at the same time the US Federal Reserve is considering raising interest rates. This is causing the euro to head lower once again. How low can the euro go? It’s been as low as 85 cents, which is roughly where Goldman Sachs thinks it can go again. Our target is $1.00 or “parity.” Right now, one euro is worth roughly $1.10. To hit our downside target, the euro would have to drop 10% from here – something we believe it can do based on relative interest rates alone. Why park cash in euros? Especially when you can get the same or better returns from the US dollar? Despite its flaws, the dollar is not only much more insulated from political risk, but it is the world’s reserve currency. Washington Post Op-Ed writer Catherine Rampell calls the euro “a weapon of mass destruction.” Nations cannot have a successful economic and currency union without a corresponding political union. Different languages, cultures and attitudes have the potential to undermine any potential progress made by a common currency. The US is a collection of UNITED STATES, not “a confederation of Independent Nations like the Eurozone. Illinois may go bankrupt, but it’s not going to dump the dollar. Social Security recipients in Illinois will still get their checks because the money comes from the Federal government. No such guarantee exists for Greece or Spain or any other European country. The dollar works because the US has a shared system of government, a shared culture and basically the same belief system. When a crisis hits one area, people can pick up and move to another where things are better. The language is the same, the history is the same. This is not how it is in Europe. Euro Works Great for Germany… The ECB is headquartered in Germany and has strong ties to German policymakers. So in practice, it tends to pay more attention to the needs of Germany than other European countries. Vox Columnist Timothy Lee explains it better than most: “Basic monetary theory says that when an economy is in a depression as severe as the one in Greece, the solution is aggressive monetary stimulus. So if you wanted to help Greece, you’d want to start printing more money in an effort to lower interest rates, boost demand, and bring down the country’s unemployment rate.” “On the other hand, if you were just focusing on the German economy, you’d reach the opposite conclusion. Germany’s economy is already booming. The economy can’t grow much faster than it already is. So more monetary stimulus will just produce inflation. You might even want to cut back to prevent the German economy from overheating…” “The problem is that the ECB is responsible for both Greece and Germany – and 17 other countries as well. The right policy for Greece will be a disaster for Germany, and vice versa.” The euro is working great for the export-driven economy of hard-driving Germany. Germany’s current account surplus – which measures how much it exports versus how much it imports – is nearly 8% of GDP. This is unheard of anywhere else in the developed world and would normally be accompanied by a much higher currency. It shouldn’t be any surprise that resentment is building in Europe. In the US, the Fed serves one master, not 17. … Not So Much for Greece, Spain & Italy Germans may be resentful they have to subsidize the Greeks, but Greeks are resentful that their own economic calamity is benefiting Germany. The euro exchange rate is far too low for the German economy. It may be too weak for Germany, but the euro is far too strong for the debt-laden economies of southern Europe. Portugal, Spain and Italy need exports to increase growth and inflation to reduce the real value of the debt on their balance sheets. The only way to get both is with a currency much weaker than the euro is now. The problem is debt. Greece, Spain, Portugal, Italy and even France are swimming in a sea of debt that has no hope of being paid off unless it is done so with much cheaper euros. Greece may be getting all the press right now, but with an economy the size of Rhode Island, Greece isn’t really that big of a problem by itself. The problem is the precedence a Greek exit sets. Until Greece, the euro was viewed as “inevitable.” But if Greece exits the euro and reverts to a massively devalued drachma, what stops Spain from reverting back to the peseta or Italy to the lira – defeating the whole purpose of the euro? Greece has a GDP of only $242 billion – 25% lower than before the crisis. Spain’s GDP is $1.4 trillion and Italy’s is 2.15 trillion, making it the third largest economy in the Eurozone. Both have far more impact in the global economy than Greece.

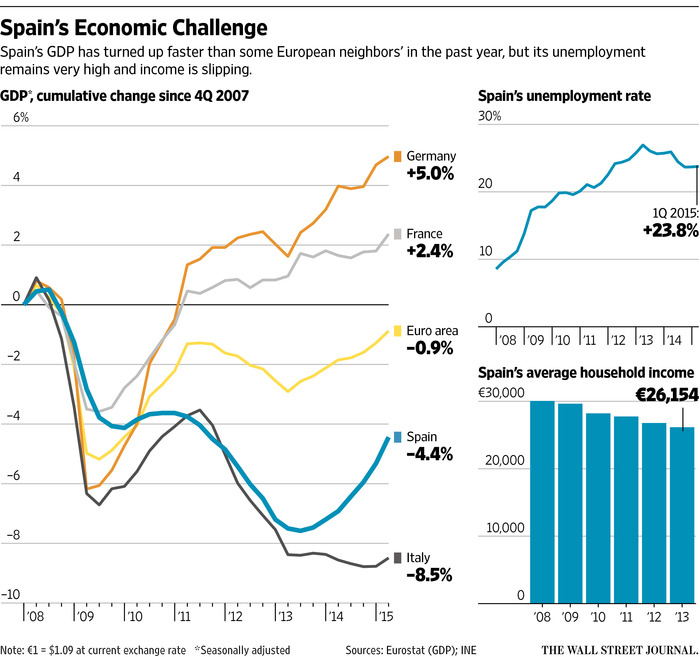

Source: Telegraph UK A decision to exit the euro by Spain or Italy could trigger chaos in the currency market. Will this happen? We hope not. But if it does, the euro’s reputation as “a weapon of mass disruption” will be well-deserved. The GDP of Italy and Spain are still below 2007 levels. Spain has one of the highest debt loads in the world when you combine public and private debt. With an unemployment rate of 24%, and elections scheduled for late December this year, Spain looks like it could be the next problem child for the EU. Restive populations make for unhappy voters. Youth unemployment is approaching 50%. No work means plenty of time to protest. The weeks leading up to and including the election could be a very interesting time for the euro. Unlike Greece, Spain’s effect on other nations in the Eurozone will be far greater. Greece may have caved to EU demands, but it wasn’t holding the same cards Spain and Italy are. In this case, size DOES matter.

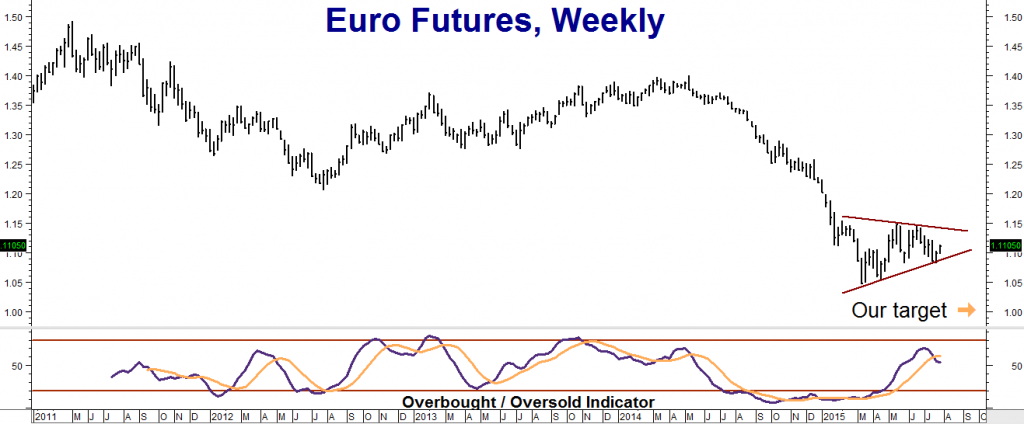

Italy doesn’t have a vote coming up this year, but it does have the slowest growing economy of the major Eurozone players. It also has the fastest rising debt in the Eurozone, increasing to 135.1% of GDP from 132.1%. Italy’s next elections are scheduled to occur before 2018, but they could get moved up should the Italian economy deteriorate further. While it may look like the Greek problem has been “solved” by keeping Greece in the euro, her issues and debts are too big to be offset by anything other than devaluation or default – and maybe a bit of both. The debt on the books of southern European countries is not going away anytime soon. Neither are the problems associated with it. This is why we believe the euro has further to fall. What to Do Now Our downside target in the euro is par. At par, 1 euro equals 1 dollar. Goldman Sachs thinks the euro could drop even further. We are recommending our trading clients use an option strategy called a bear put spread to take a short position in euro. We are going to use the March options on the euro to make our trade. These options don’t expire until early March 2016, keeping us short through December’s election in Spain. The “bear put spread” we are recommending currently costs $800 plus transaction cost. This is the most we can lose if filled at our price. If we are right and the euro declines to or below $1.00 by March 4, 2016, this “bear put spread” could be worth as much as $5,000 for each one we hold. When we buy the bear put spread, we are paying money for the right, but not the obligation, to be short the euro at a price of $1.0400 and simultaneously receiving money for the obligation to be long the euro at $1.0000. We use the money we receive for our obligation to be long at $1.0000 to partially offset the money we’ve paid to be short at $1.0400. This reduces both the cost of the trade and our “out of pocket” risk. We can make the 400 point (4 cents) difference between our right to sell the euro at $1.0400 and our obligation to buy it back at $1.0000, but no more. Multiply 4 cents times the €125,000 contract size and you get a gross profit potential of $5,000 per spread. Subtract the $800 cost of the trade to get a net profit potential of $4,200. One of the best things about this strategy is its low cost and limited risk. All we can lose, even if we are dead wrong, is the $800 (plus transaction costs) we pay for our spreads. This gives us the ability to weather any temporary price swings. We can “set it and forget it.” By using this insider’s approach to foreign currencies, we get big potential and peace of mind. Trading customers should call their personal RMB Group broker for all of the details of this trade. If you don’t have an RMB Group trading account and would like to know more about this or any other “Big Move” strategy, call 800-345-7026 toll free or 312-373-4970 direct. You can also email suerutsen@rmbgroup.com to get more information or visit us online at www.rmbgroup.com. |